手机游戏为什么要做性能优化?

为什么越来越多的手机游戏在关心性能优化?应该如何关注和做性能优化呢?

性能话题应该是近两年手游圈里最热门的话题之一了。

随着手机游戏开发管线的不断成熟,越来越多的事情开始需要专业化和精细化,比如几年前的TA。现在,手游的性能优化逐渐也开始成为一个独立的岗位,甚至可以和TA、图形程序员待遇相当。这导致的影响就是游戏程序员的分支路线开始呈现多元化。

而对于绝大多数的程序员可能只能走前两条路线了。相对而言下面这个方向都需要有一定的横向能力,尤其是管理岗位,对于交际和沟通有着相当大的要求。

TA和引擎有一些共同点,都需要丰富的图形知识,但不同的是TA现在是归属在美术组的,这个岗位是一个偏业务向的也就是解决实际项目问题的岗位,另外因为归属于美术组,所以一定程度上TA还偏设计向。也就是说,一些表现方案应该是由Ta进行技术和原型验证,没问题之后再由前端程序进行接入整合。

而引擎程序员则偏向于架构向的。也就是说这些图程会制定渲染管线,搭建渲染架构,这些内容往往会脱离具体业务,而成为公司/行业标准的一个部分。

如果要举个例子的话,可以认为图形程序员是编写photoShop的岗位,而TA是使用PS做海报和设计的岗位。最后前端程序员会拿着TA做的海报,根据实际的张贴需求,打印不同的大小,甚至裁剪其中的一些部分。

当然这个比喻不一定恰当,但基本可以描述图程和TA的关系。

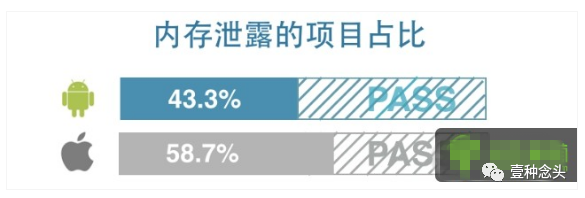

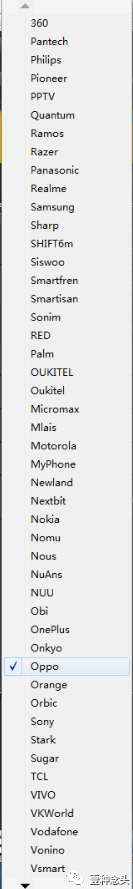

那么接下来就是现阶段最火的岗位,性能优化了。个人觉得催化这个岗位的主要原因还是因为商业引擎越来越成熟,手游开发客户端的门槛越来越低导致的。当然另外一个原因还是因为当前国内的游戏市场的版号限制,导致越来越多的公司要做出海计划。既然要出海,那就不能只考虑欧美国家,像东南亚,印度,巴西等比较落后和贫穷的国家也是需要考虑的,甚至很多时候是优先考虑的(主要原因还是推广成本低,导量便宜)。

门槛低导致越来越多的Game Play程序员无法理解商业引擎的实现原理,甚至培训几个月就来上岗,写出来的代码几乎是属于灾难性的。而出海贫穷地区则因为手机设备的落后,低端导致游戏必须要严控性能才有可能在落后国内5年的硬件上跑起来。

这个时候必须要有一个人能够挑起性能这个大梁,达成一夫当关万夫莫开的气势。所有有性能问题的设计、代码或者实现统统在这里被挡回去。但这说的很容易,够资格胜任的人却很少。和TA、图程的专业知识不一样,性能岗位需要精通的是引擎和实现。

这就要求:

1 需要对引擎使用有较高的熟练度。这就隐性的要求该岗位人员的从业和引擎使用年限、项目经历、解决方案和见识、引擎的各种设置和实现原理等。

2 扎实的基础和基本功。引擎再好也需要自己写代码。如果不了解自己语言的特性、设计模式、数据结构等就没有办法检查除别人代码里的深层次原因。

有人可能会好奇,难道主程不能做吗?一般能当主程的技术肯定都还行啊。额,我的结论是,哪怕主程合格能cover,他也不应该去做。因为管理岗和技术岗是独立区分的岗位,它们有不同的岗位职责。对于主程而言,更多的工作是怎么分配协调任务,怎么保障进度,怎么做技术沉淀和人员梯队。有机会我们可以专门聊聊主程应该做什么。但现在要理解的话,可以打一个简单的比方,主程好比是班主任/辅导员,班主任首先自己是个老师,当然也会教自己擅长的科目,但更多的精力还是放在怎么提高班级整体水平上。

说回性能优化这个岗位,我们组里的岗位我设定的职责为,不做具体开发业务,只负责规划、查找、解决项目中的性能问题。也就是什么都不做,又什么都要做。

好了,累死我了,终于能说,什么是性能问题了。

所有的性能问题都可以归结于一句话:硬件受委屈了。

1 它们承担了它们这个级别不应该有的压力。 例如,CPU计算压力过大,GPU的绘制压力过大,CPU和GPU数据交互过大,过频繁,内存消耗太大等等。

但是造成这些硬件委屈的原因则有很多很多种情况。比如,CPU的委屈可能来自于,不合理的代码循环,不必要的逻辑运算,频繁的内存申请导致的GC,过多的蒙皮动作,大量的粒子计算,超多的物理模拟,超多、超大的文件加载等等。

内存的原因可能来自,过大的纹理、资源、文件、数据,过多的托管内存申请,不恰当的内存管理和释放机制,不恰当的缓存管理,过多的SDK和工具引入,冗余的三方代码和库,没有做变体剥离的Shader等等。

GPU的问题则可能来自于,过多的顶点和三角面,过多的OverDraw,过大的纹理,过复杂的Shader计算,过多的纹理采样,复杂的后处理效果等等。

(Upr的GPU页签,关于GPU的一些常用参数)

2 它们没有受到应有的尊重。 也就是说,本来我可以做的更好,但是由于你不懂我,或者你的失误,导致我的能力没有得到最佳发挥(喂,不是这么用的!)。

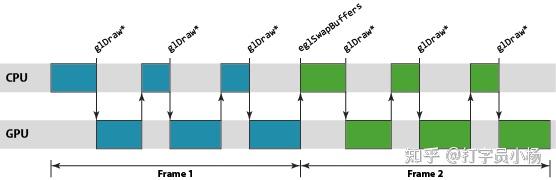

最典型的就是DrawCall。大部分都知道DC越高,性能越差,却有很多人无法真正回答正确DC高为什么会有性能问题(至少我面试过的人里占一大半),实际上它最大的原因是因为GPU需要等待,也就是处于空闲状态。

另外一个就是不同类型的GPU纹理格式压缩,大家或许都知道,要把纹理设置成ETC1,ETC2,ASTC,PVRTC,却很少人(我面试过的人中)知道为什么。

还有对于Mono内存的申请机制不了解,就不知道为什么要先申请大内存的,然后再申请小内存等等。

知道了性能问题的根源,也知道造成性能问题的原因,那么怎么样把它们和具体的表现挂上钩,从而能够快速排查性能问题呢?或者说,有关于性能问题的具体表现是啥,怎么样才知道项目遇到了性能问题?

这里我把性能问题的具体表现总结为两个方面, 卡和慢 。

卡表现在那些地方?当你打开某个界面的时候,界面是一顿一顿的从边缘滑动进来,或者打开之后过比较长时间才能加载出来。

进入一个场景的时候,loading了很久,进度条一直不动,进入场景之后,看别人走路跟滑冰一样。

手机发烫,耗电量急剧增加,运行的好好的突然ANR一下。

一到团战闪退了。要么就是卡死不动了。

更极端一点,场景其他地方都很流畅,只要一到这个水坑边上就掉帧。

更早的时候,流量资费没降下来之前,数据流量也会算作性能的一个部分。

但这里要提一嘴,并不是只要遇到上述情况就归于性能问题。游戏开发一般会有一个参照的适配机型,分为高中低配三个档次。中配就是要能够展现出所有项目预期的设计和效果。而高配会在中配的基础上适当调高效果和帧率,比如增加描边,更好更好的纹理,更多更华丽的特效等等。而低配机型,我们一般只保证功能,不保证效果。

那些比低配机型更低的,就不会考虑了,能玩你就将就玩,不能玩请你换机器。

也就是说,很多的性能其实是和参照机型挂钩的。举个例子,PSS(实际使用的物理内存)在中配机型上占800M,2020年的中配机1500-2000元,内存怎么也的有个4G了,哪怕只有2G压力也不大。所以这个指标我们再中配机型上是能接受的。

但是,这个指标在我们的低配机型上就不能接受,我们现在的低配机型可能就是东南亚的平均水平,所以有可能会它会跑在内存只有1G的低端机器上。800M的PSS极容易造成闪退。这个时候,我们的性能优化就需要上场,针对低端机型做内存方面的优化。

这些优化的策略有的是基于整体的,也就是说,高中低配都受用,有些仅仅是针对机型的,比如换一些精度更低的纹理,减少一些不必要的装饰加载,限制同屏显示的内容等等,具体手段需要因项目而异。

抓取性能问题的工具有很多,最常用的是Unity自带的两个。

Porfiler可以调试很多模块的参数,但我基本上用它抓CPU和内存。另外要说一下的是,因为Editor本身会占用很多额外消耗,所以直接用编辑器调试需要自己能排除掉Editor自身的干扰,也就是说你看的问题可能在实际机器上并没有,又或者没有这么凸显。最准确的方式就是用真机调试,但大多时候性能点并不会转移,只是精确度的问题,所以开发时候用编辑器调试定位问题,然后修改之后在真机验证。

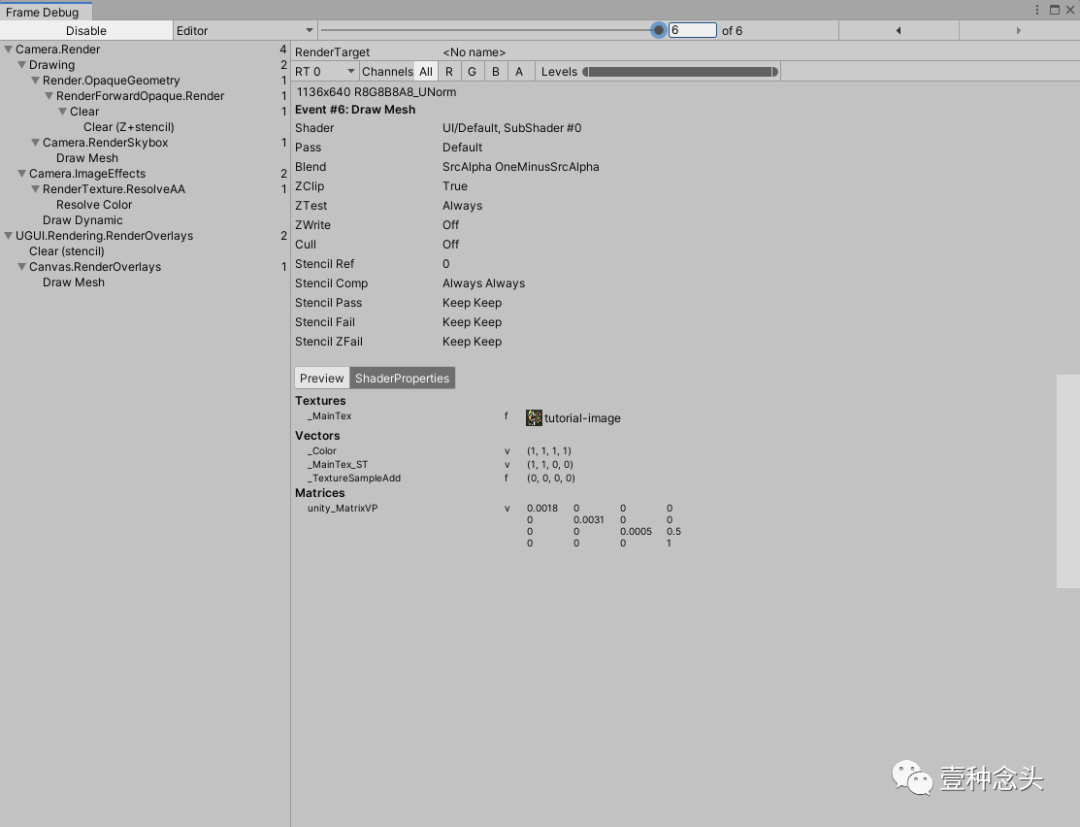

自带的第二工具是FrameDebug

这是用来调试渲染的,在这里可以逐帧的调试渲染,看到每一帧的渲染数据。比较适用于有一定图形知识和能力的人,比如TA和懂图形知识的程序员。他们可以在这里查看到,实际的渲染情况是否超出了预期,比如该合批的没有合批,原因是啥。

另外也建议一些UI经验丰富的人学会查看UI层面的DrawCall情况,从而减轻UI部分的渲染压力。

另外也可以给大家推荐一下UWA的几个测试工具。

这些工具都是基于真机运行收集的数据,准确度高,维度也多。尤其是GOT,如果团队有性能解读能力,这个工具的性价比是最高的,一次付费之后可以一直使用。

UWA是很老牌的性能优化服务商,做的时间久,经验丰富。除了本地测试产品之外,他们也有云端测试产品和驻场服务。

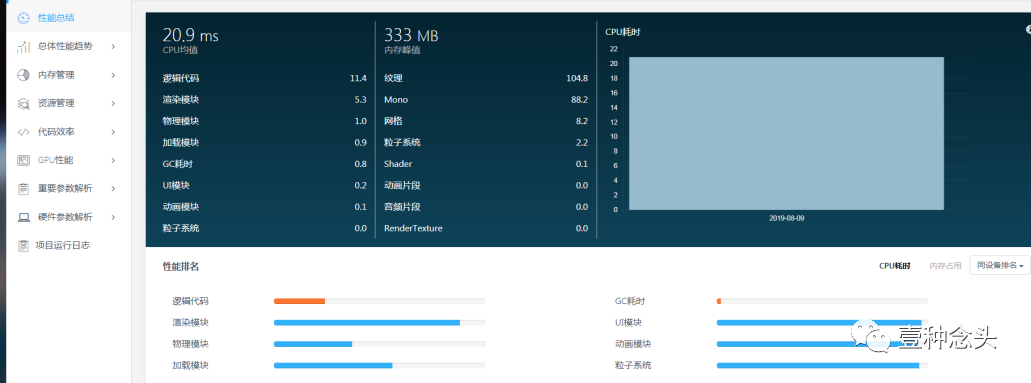

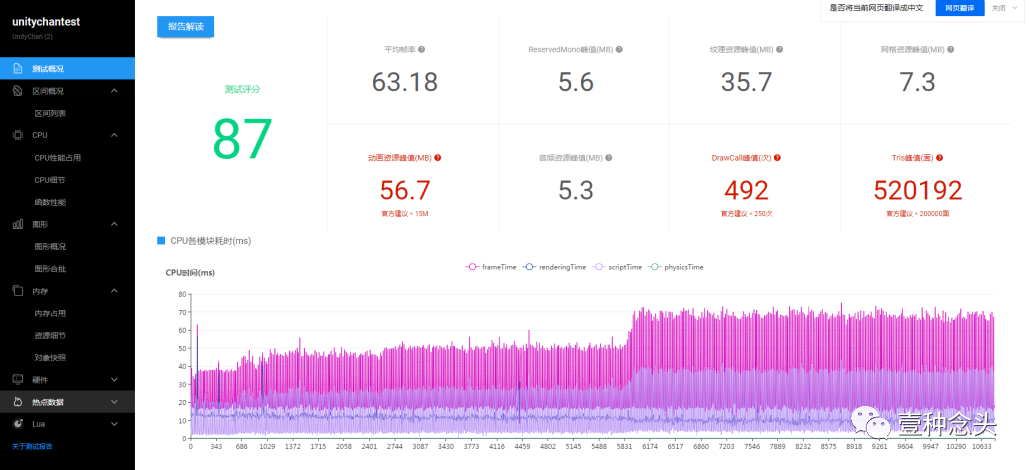

云测试就是你们提交包给他们的网站,他们会使用真人帮助测试,然后生成一份性能报告。性能测试报告大概长下面这样子:

报告分为免费报告和专业报告。专业报告参数更多,更全面,会有专门的专家负责解读。但免费报告他们其实服务的也很好,基本上会基于报告的数据给与一些意见和建议。

第二个是Unity自己的UPR服务。这个是目前Unity正在做的方向,大概也是未来侑虎强有力的竞争对手。他们的测试方式和侑虎略有不同,侑虎是提交包之后,相关人员对接确定哪些地方重点测试,然后由侑虎人员去跑然后生成报告,也就是托管测试。而UPR是给了两种工具,一种是基于PC的,一种是真机APP的,你可以通过这两个工具自己去跑,然后上传测试数据,网站后台生成报告数据。

UPR的报告没有分免费和付费,但同样也不提供对接和基础解读,如果要解读需要付费(和侑虎付费模式一样)。另外还有一点,UPR现在是全免费,不限次数的。UWA的免费每个月一次并且提供基础解读。所以,我觉得大家选择的时候,要根据自己团队的能力,看看选哪个更好。

第三个是Unity和UWA都有的驻场优化服务,主要就是给没有能力做优化的团队,查找、分析项目问题,以入驻的形式,帮项目把性能点摆平,这个我没用过,在次就不多介绍了。

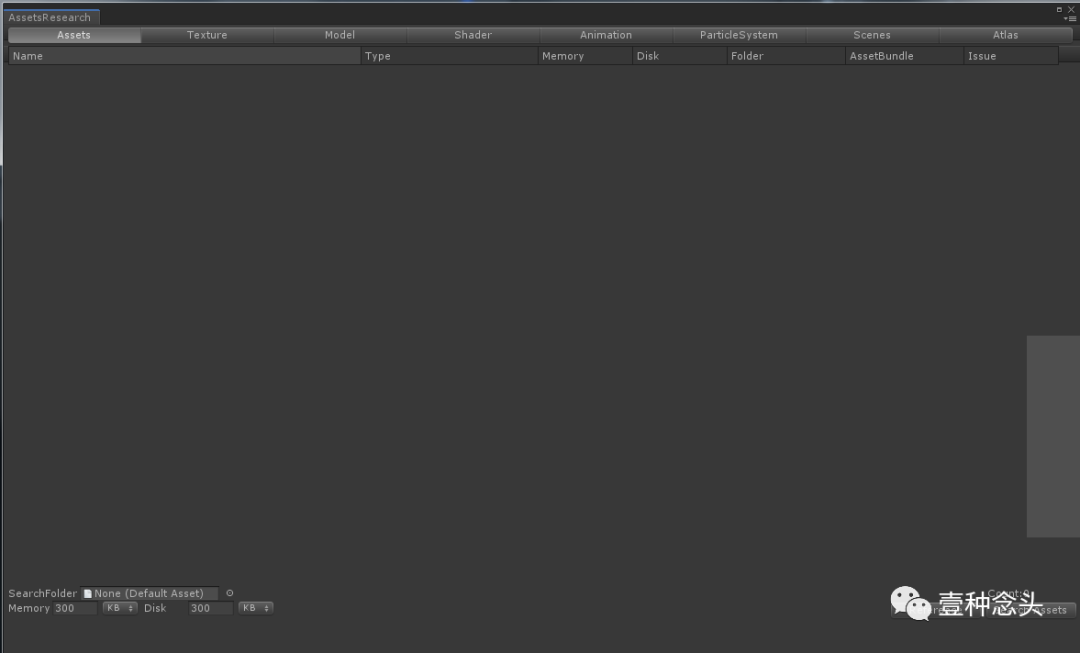

除了Unity自有的工具和第三方工具之外,也可以根据需要自己创建工具。基于ScriptImporter,我们可以写很多自动化监测和修改的脚本。同时也可以利用Unity Editor下的一些API完成对资源的检测。下面就是我们团队自己写的针对各种美术资源或者的查询和监测。

说到这,我说个比较有意思的工具,因为要做低端机的分段适配,我们需要有一套算法来推测机型属于哪一档。组里的小伙伴很给力,自己写了爬虫,爬了市面上大部分安卓机器的型号和数据,然后做了一个工具和评分提供给策划和QA,让他们能够快速的判别一个机器属于哪一档。

性能的话题暂时先聊这么多,我大概会写一个基于性能的系列,会详细聊聊各种性能相关的问题。另外,推荐一下本人的教程汇总:

放牛的星星:[教程汇总+持续更新]Unity从入门到入土——收藏这一篇就够了希望能对一部分人有所帮助。

提供一个与众不同的视角吧

国内很多公司并不重视技术积累,但是重视性能优化

所以很多想走技术路线的人会鼓动公司做性能优化

公司也容易接受

不要谈什么生产力,造轮子,砸几个月进去

就说,你的产品多烂的机器能跑吧,市场运营老板都爱听这个

国内的游戏性能优化,是把很多公司产品引上技术正途的一个通道

这方面做起来的公司,典型的是UWA。你可以想象一下,如果UWA是个Unity,Unreal,或者小些级别的,比如当年的微云木瓜之类的,在国内会遇到什么情况……

有时候你会找到一些很有意思的文章,你想研究一下,但是现在还没时间,但是又怕过一阵子人家网站关门大吉了,于是先把它们收录在这里,以后有时间了再研究。我会放上原文链接,如果大家看到感兴趣,想一起研究的话,也可以私密我,我们一起研究研究。

Optimization of graphics workloads is often essential to many modern mobile applications, as almost all rendering is now handled directly or indirectly by an OpenGL ES based rendering back-end. One of my colleagues, Michael McGeagh, recently posted a work guide on getting the Arm DS-5 Streamline profiling tools working with the Google Nexus 10 for the purposes of profiling and optimizing graphical applications using the Mali-T604 GPU. Streamline is a powerful tool giving high resolution visibility of the entire system’s behavior, but it requires the engineer driving it to interpret the data, identify the problem area, and subsequently propose a fix.

For developers who are new to graphics optimization it is fair to say that there is a little bit of a learning curve when first starting out, so this new series of blogs is all about giving content developers the essential knowledge they need to successfully optimize for Mali GPUs. Over the course of the series, I will explore the fundamental macro-scale architectural structures and behaviors developers have to worry about, how this translates into possible problems which can be triggered by content, and finally how to spot them in Streamline.

The most essential piece of knowledge which is needed to successfully analyze the graphics performance of an application is a mental model of how the system beneath the OpenGL ES API functions, enabling an engineer to reason about the behavior they observe.

To avoid swamping developers in implementation details of the driver software and hardware subsystem, which they have no control over and which is therefore of limited value, it is useful to define a simplified abstract machine which can be used as the basis for explanations of the behaviors observed. There are three useful parts to this machine, and they are mostly orthogonal so I will cover each in turn over the first few blogs in this series, but just so you know what to look forward to the three parts of the model are:

- The CPU-GPU rendering pipeline

- Tile-based rendering

- Shader core architecture

In this blog we will look at the first of these, the CPU-GPU rendering pipeline.

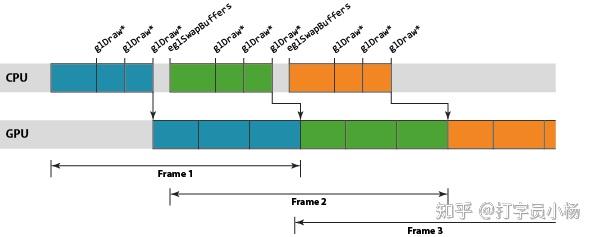

The most fundamental piece of knowledge which is important to understand is the temporal relationship between the application’s function calls at the OpenGL ES API and the execution of the rendering operations those API calls require. The OpenGL ES API is specified as a synchronous API from the application perspective. The application makes a series of function calls to set up the state needed by its next drawing task, and then calls a glDraw[1]function — commonly called a draw call — to trigger the actual drawing operation. As the API is synchronous all subsequent API behavior after the draw call has been made is specified to behave as if that rendering operation has already happened, but on nearly all hardware-accelerated OpenGL ES implementations this is an elaborate illusion maintained by the driver stack.

In a similar fashion to the draw calls, the second illusion that is maintained by the driver is the end-of-frame buffer flip. Most developers first writing an OpenGL ES application will tell you that calling eglSwapBuffers swaps the front and back-buffer for their application. While this is logically true, the driver again maintains the illusion of synchronicity; on nearly all platforms the physical buffer swap may happen a long time later.

The reason for needing to create this illusion at all is, as you might expect, performance. If we forced the rendering operations to actually happen synchronously you would end up with the GPU idle when the CPU was busy creating the state for the next draw operation, and the CPU idle while the GPU was rendering. For a performance critical accelerator all of this idle time is obviously not an acceptable state of affairs.

To remove this idle time we use the OpenGL ES driver to maintain the illusion of synchronous rendering behavior, while actually processing rendering and frame swaps asynchronously under the hood. By running asynchronously we can build a small backlog of work, allowing a pipeline to be created where the GPU is processing older workloads from one end of the pipeline, while the CPU is busy pushing new work into the other. The advantage of this approach is that, provided we keep the pipeline full, there is always work available to run on the GPU giving the best performance.

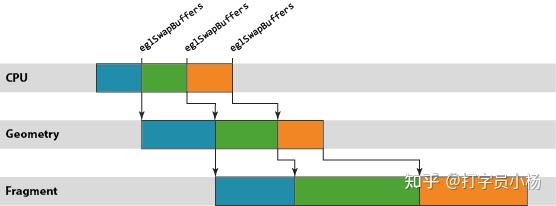

The units of work in the Mali GPU pipeline are scheduled on a per render-target basis, where a render target may be a window surface or an off-screen render buffer. A single render target is processed in a two step process. First, the GPU processes the vertex shading[2]for all draw calls in the render target, and second, the fragment shading[3]for the entire render target is processed. The logical rendering pipeline for Mali is therefore a three-stage pipeline of: CPU processing, geometry processing, and fragment processing stages.

An observant reader may have noticed that the fragment work in the figure above is the slowest of the three operations, lagging further and further behind the CPU and geometry processing stages. This situation is not uncommon; most content will have far more fragments to shade than vertices, so fragment shading is usually the dominant processing operation.

In reality it is desirable to minimize the amount of latency from the CPU work completing to the frame being rendered – nothing is more frustrating to an end user than interacting with a touch screen device where their touch event input and the data on-screen are out of sync by a few 100 milliseconds – so we don’t want the backlog of work waiting for the fragment processing stage to grow too large. In short we need some mechanism to slow down the CPU thread periodically, stopping it queuing up work when the pipeline is already full-enough to keep the performance up.

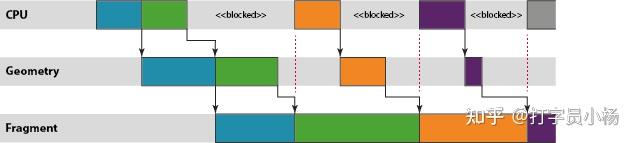

This throttling mechanism is normally provided by the host windowing system, rather than by the graphics driver itself. On Android for example we cannot process any draw operations in a frame until we know the buffer orientation, because the user may have rotated their device, changing the frame size. SurfaceFlinger — the Android window surface manager – can control the pipeline depth simply by refusing to return a buffer to an application’s graphics stack if it already has more than N buffers queued for rendering.

If this situation occurs you would expect to see the CPU going idle once per frame as soon as “N” is reached, blocking inside an EGL or OpenGL ES API function until the display consumes a pending buffer, freeing up one for new rendering operations.

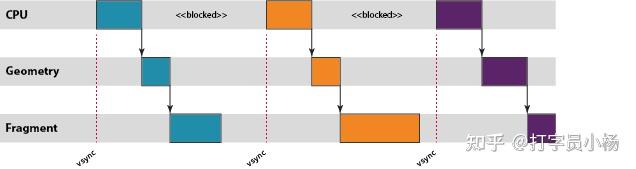

This same scheme also limits the pipeline buffering if the graphics stack is running faster than the display refresh rate; in this scenario content is "vsync limited" waiting for the vertical blank (vsync) signal which tells the display controller it can switch to the next front-buffer. If the GPU is producing frames faster than the display can show them then SurfaceFlinger will accumulate a number of buffers which have completed rendering but which still need showing on the screen; even though these buffers are no longer part of the Mali pipeline, they count towards the N frame limit for the application process.

As you can see in the pipeline diagram above, if content is vsync limited it is common to have periods where both the CPU and GPU are totally idle. Platform dynamic voltage and frequency scaling (DVFS) will typically try to reduce the current operating frequency in these scenarios, allowing reduced voltage and energy consumption, but as DVFS frequency choices are often relatively coarse some amount of idle time is to be expected.

In this blog we have looked at synchronous illusion provided by the OpenGL ES API, and the reasons for actually running an asynchronous rendering pipeline beneath the API. Tune in next time, and I’ll continue to develop the abstract machine further, looking at the Mali GPU’s tile-based rendering approach.

Comments and questions welcomed,

Pete

- [1]There are many OpenGL ES draw functions which draw things, it doesn't really matter which one you pick for this example.

- [2]Vertex (computer graphics) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- [3]Fragment (computer graphics) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

在做的项目定位大DAU手游,性能控制的比较紧,基本上不能使用Niagara系统做效果。但这并不意味着效果追求就没有了,我们仍然在追求一种小而美的精致感,不想要薄气的感觉,也不想充斥着光污染的廉价特效。那么物理解算是非常必要的,使得每种表现都是有着落的,符合日常经验的。所以VAT是很合适的技术手段。

将顶点位移信息储存至一张16位贴图中,通过采样播放预处理的动画信息,使其不用实时演算。

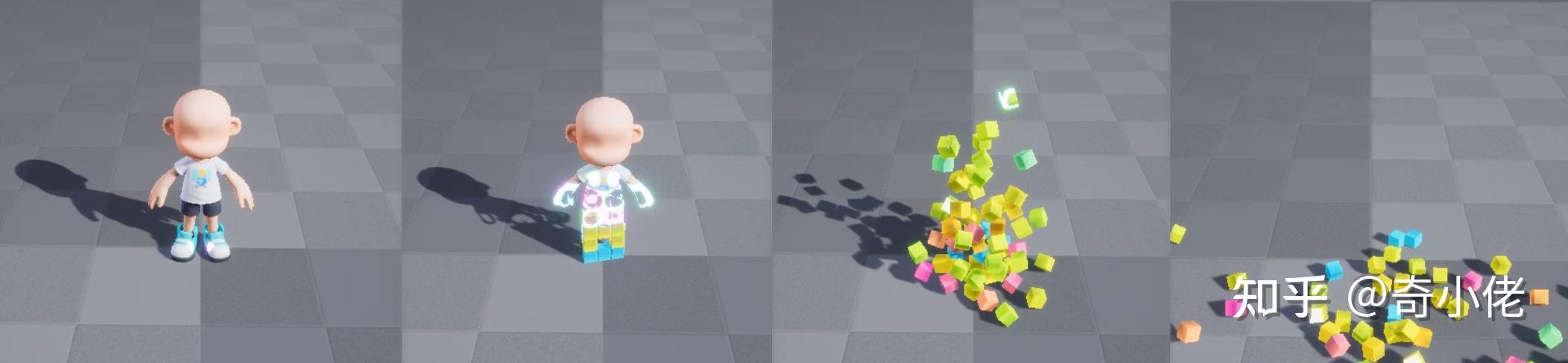

最终效果https://www.zhihu.com/video/1724777656887967744

最终效果https://www.zhihu.com/video/1724777656887967744核心思路:

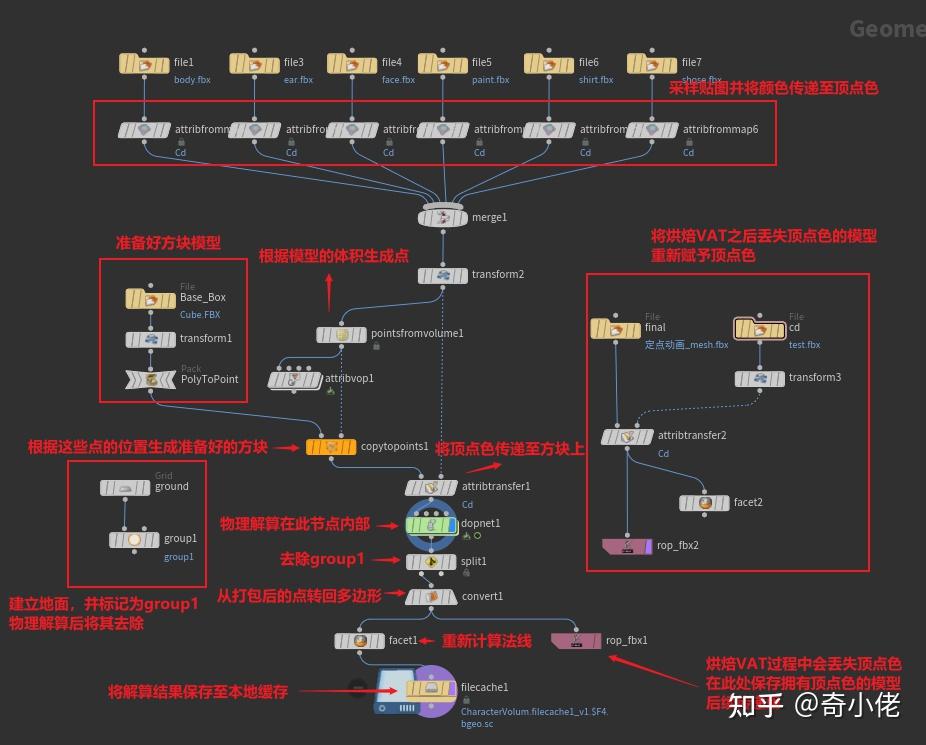

1、根据角色形体生成方块模型

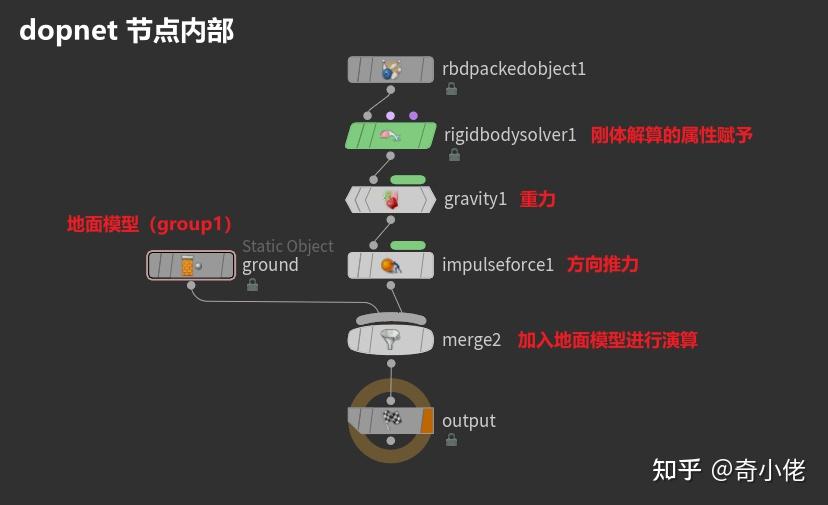

2、用物理解算生成方块坠落动画

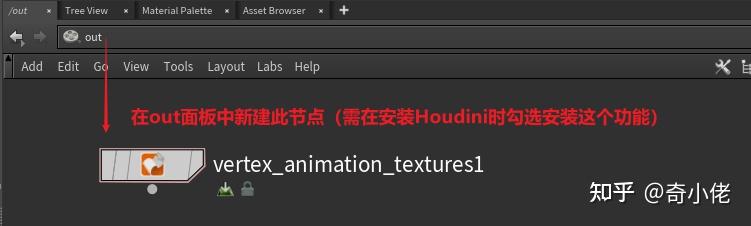

3、烘焙模型与VAT贴图

4、UE端材质适配

Houdini端:

Unreal端:

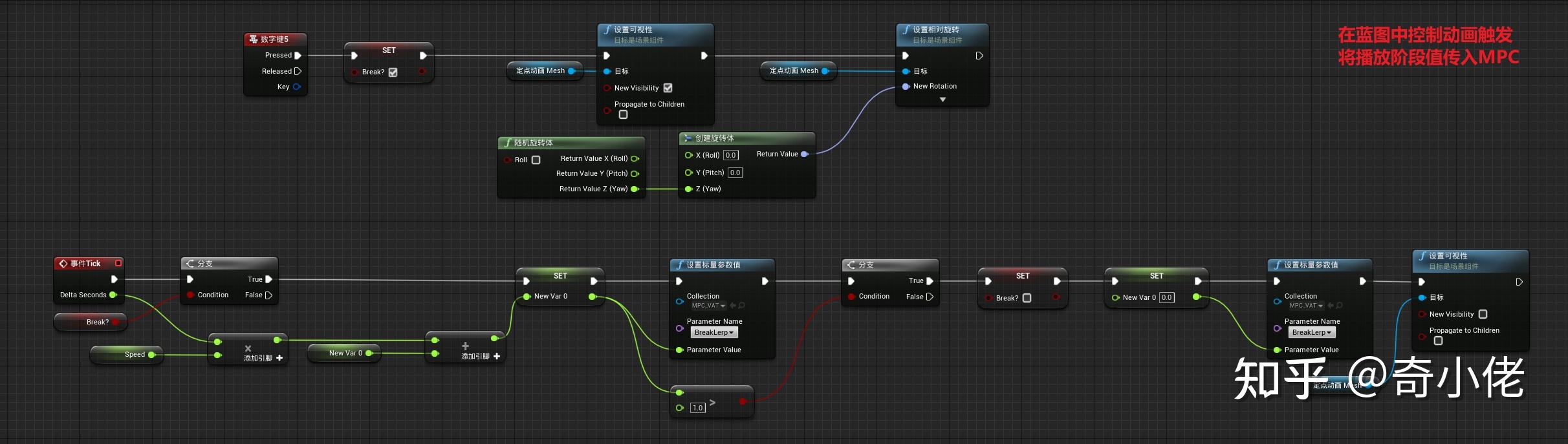

角色蓝图:

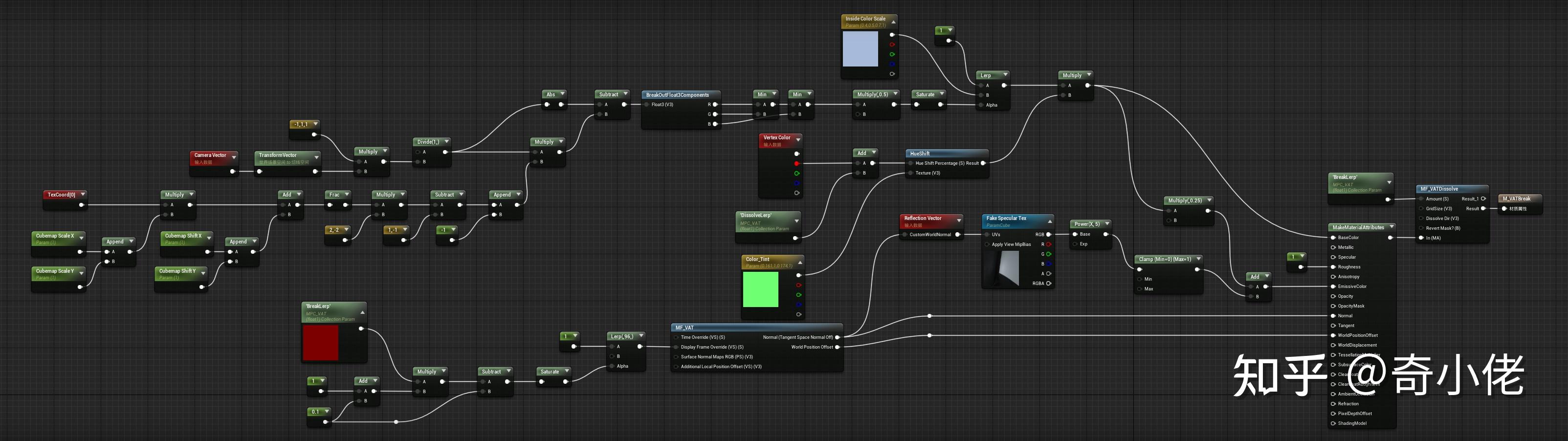

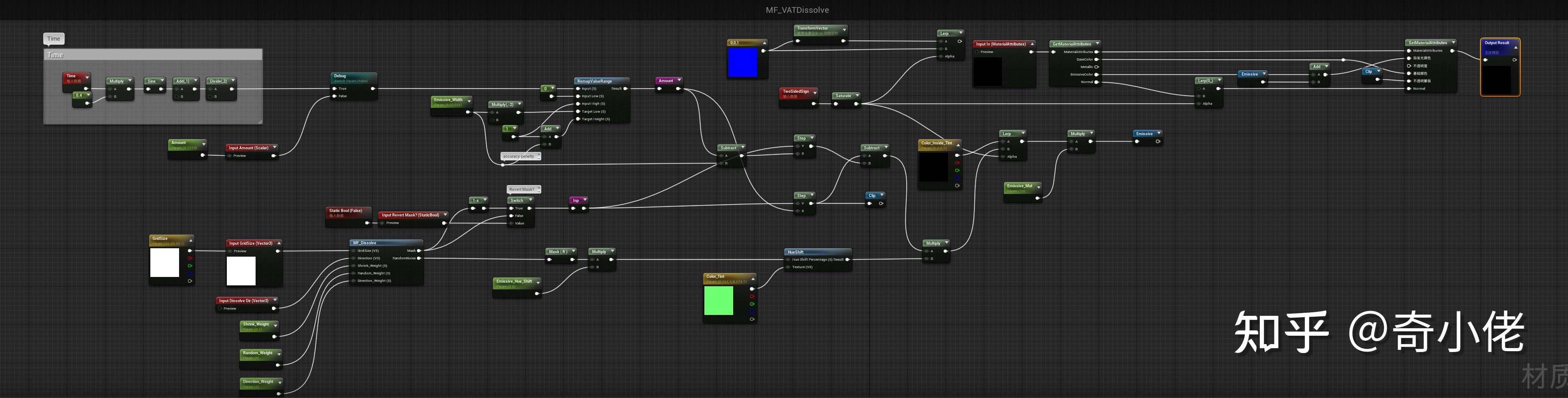

方块材质:

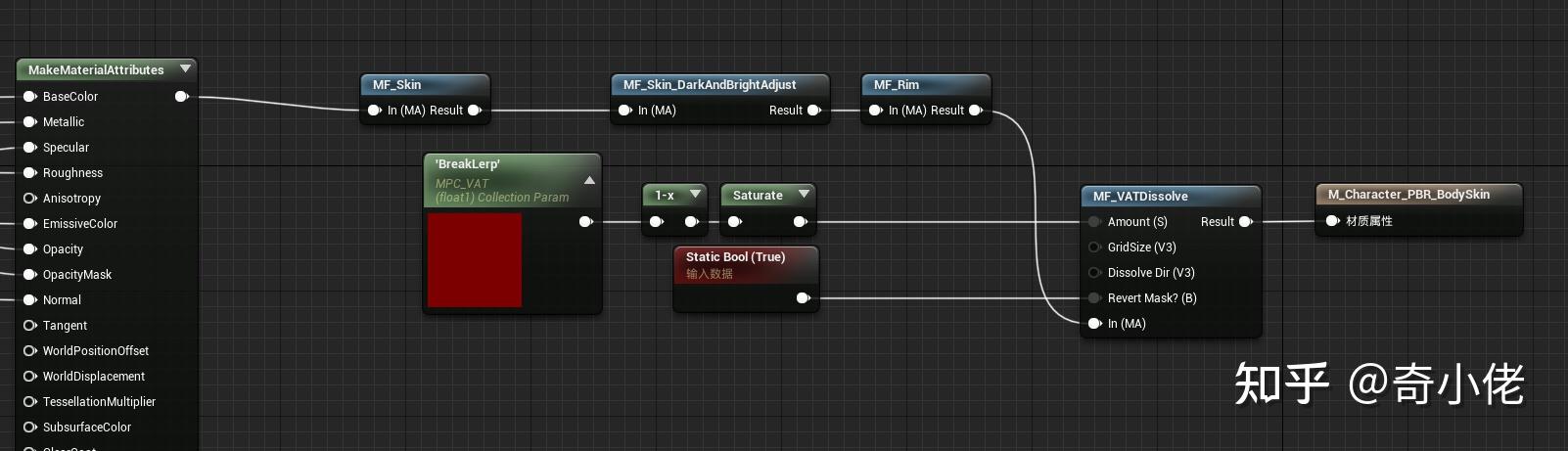

角色材质:

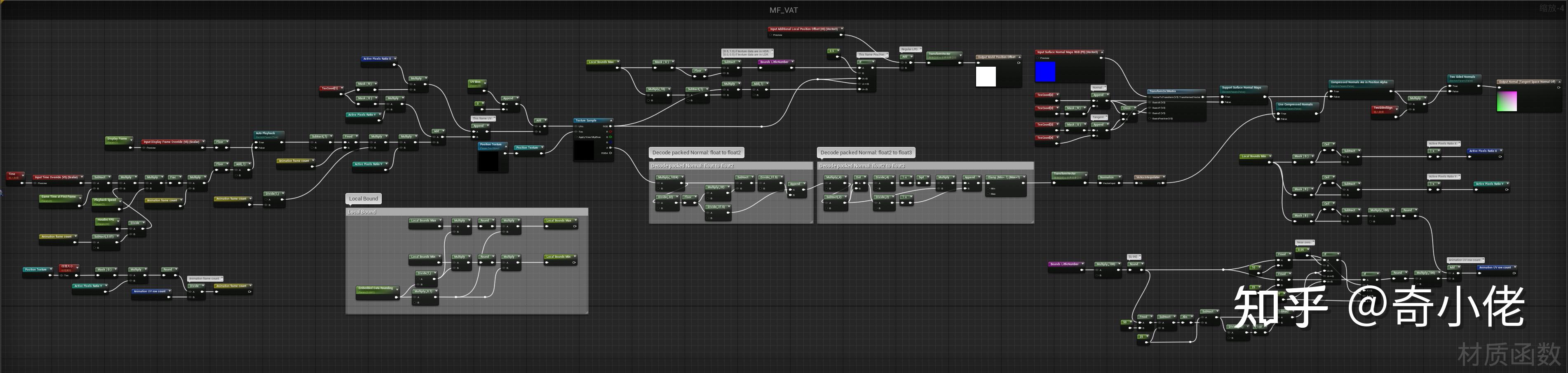

VAT材质函数:

溶解效果材质函数:

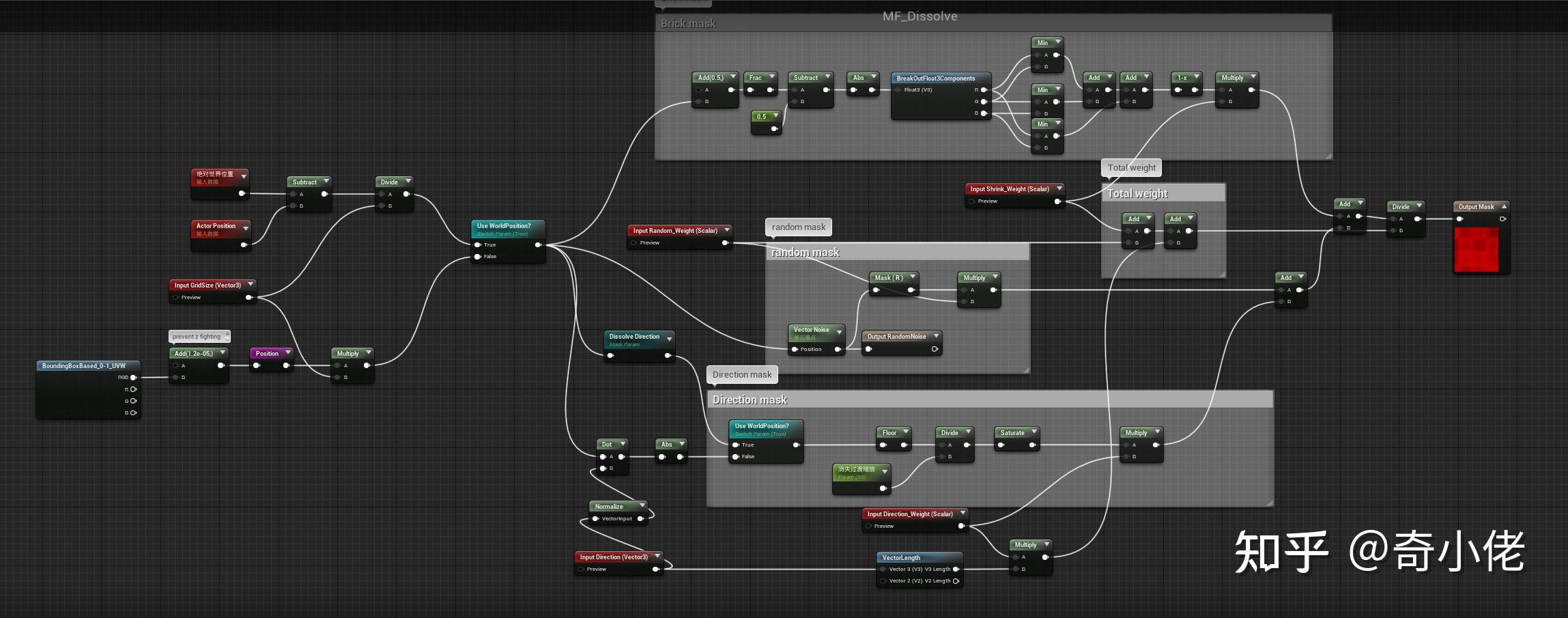

溶解MASK材质函数:

推荐其他Trick案例:

奇小佬:TA案例:假磨砂玻璃材质的设计与制作